[Last updated: 16 October 2020]

Johan Friederich Stembel (Great-Grandfather)

Frederick Stembel (Grandfather)

Henry Stembel (Father)

Roger Nelson Stembel

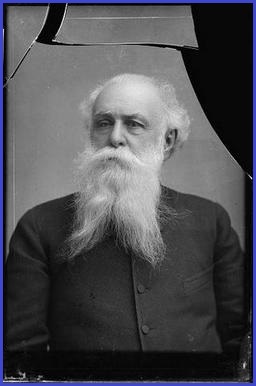

Roger Nelson STEMBEL (1810 - 1900)

Roger Nelson Stembel is the most notable descendent of Johan Friederich Stembel, by a large margin. He attended college at a time when few did, he then joined the Navy, and saw action in two wars. In the Civil War his leadership was praised by Gen. Grant, and at the battle for Fort Henry, he was the Union officer who accepted the Confederate's surrender of the fort. Three months later, he was nearly mortally wounded in a gunboat fight on the Mississippi River, but survived, returned to duty after the war and eventually attained the rank of Rear Admiral. In 1864 President Lincoln proposed that Congress give him a vote of thanks for his service. In 1943, forty-three years after Roger's death, a new Fletcher-class destroyer was named in his honor, the USS Stembel.

Roger was the only son of Henry Stembel, an ambitious man who distinguished himself in the War of 1812. After the war Henry lobbied the Secretary of War to accept his service as an officer in the Army. The army, however, was downsizing and his offer was turned down, so Henry moved on. I don't know how much his father's love of the military influenced Roger's decision to make the Navy his profession, but he was obviously well prepared for it.

Roger was the only son of Henry Stembel, an ambitious man who distinguished himself in the War of 1812. After the war Henry lobbied the Secretary of War to accept his service as an officer in the Army. The army, however, was downsizing and his offer was turned down, so Henry moved on. I don't know how much his father's love of the military influenced Roger's decision to make the Navy his profession, but he was obviously well prepared for it.

Roger Nelson Stembel was born December 27, 1810,(1) in Middletown, Maryland. When he was about 8 years-old, his family moved to Georgetown, in the District of Columbia, where they lived for about 8 years. In 1824, Roger applied for admission to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He was 14-years-old at the time. One could see the hand of his father in this decision, for his father was now going by the name Col. H. Stembel. Evidently Roger was not accepted.Sometime around 1826 Roger's father moved the family to Dayton, Ohio, where Roger was likely enrolled in the Dayton Academy. Soon after the move we believe, Roger bought 240 acres of land from the Cincinnati land office(2). He was not yet 16-years-old. The land was located just north of Dayton, now located right in the middle of Dayton's International Airport.

In 1827 Roger enrolled in Miami College (now Miami University), in Oxford, Ohio(3). During the fall of 1829, Roger's father died suddenly on a trip back to Maryland.

Roger graduated in 1832 at the age of 21. A year later, Roger received an appointment as a midshipman in the U.S. Navy. He saw service in the Second Seminole War in 1836 and was promoted to Passed Midshipman in 1838. In 1842 Roger was again promoted, to Lieutenant. A year later, he married Laura McBride of Hamilton, Ohio, a town about 12 miles southeast of Oxford and Miami College.

Laura was the daughter of James and Hannah McBride, prominent citizens of Hamilton. James McBride was an architect by trade but was fascinated by history, law, math, and science. He spent considerable time conducting research and wrote extensively. He and Roger carried on a lengthy correspondence. James made copies of his letters to Roger and saved all of Roger's return letters. Eventually he had these letters bound. Most of these volumes are available for review at the Cincinnati Historical Society (Note: I have not been able to locate these. The Cincinnati Historical Society is now part of the Cincinnati Museum)(4). Laura was well educated, unusual for a woman of her time. A biography of her father states she attended the Female Athenaeum at Hygiea Farm, and the Hamilton and Rossville Female Academy.

Laura and Roger had two children, Clara, born in 1844, and James, born in 1846. The same year that James was born, Roger nearly lost his life when the ship he was serving on was caught in a hurricane off Nags Head, North Carolina. A full account of that event can be found here.

In late summer of 1857, Lt. Roger Stembel was an officer onboard one of the ships that sailed to China carrying William B. Reed, United States Plenipotentiary (our ambassador), who headed a delegation who would eventually meet with Tau Tingsiang, the Imperial Chinese Commissioner, to negotiate a revision to our treaty with China(5). Roger was selected to sit in on the negotiations. It appears the delegation spent months anchored in Chinese ports (Hong Kong, Macau) determining the political climate and making contacts with the Chinese government, before the actual negotiations took place in May 1858. It must have been an interesting experience to visit a country most Americans knew little about, while at the same time boring to spend months on board ship with little to do.

With the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1859, southern slaves states left the Union to form their own country. This was a critical time for our armed forces as some, from all ranks, left to join the South, while at the same time knowing war was almost certain. The Union Navy began preparing for it. Though Roger was born in a slave state and his father had owned slaves, he pledged his loyalty to the Union. In 1861, he was promoted to Commander and assigned special duty in Cairo, Illinois. His assignment was to help oversee the building and testing of a flotilla of Union gunboats, both timberclads and ironclads, to patrol the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Gaining control of the Mississippi River was crucial to winning the war. To that end, the federal government funded a crash program to build a fleet of gunboats, and Roger was assigned to work with the contractor, James B. Eads, to advise and test the boats as they were built. James Eads was a daring and inventive civil engineer who went on to become one of the foremost civil engineers in the world.

In 1863, a letter from Roger to James Eads implies James had asked Roger for a detailed account of Roger's experiences with the ships he designed. Roger began his nine page letter with "My Dear Friend,...". His signature at the end of the letter can be seen at the top of this page(6).

Once the initial flotilla was ready and assembled, Roger was placed in command of the timberclad gunboat Lexington, and the small gunboat flotilla began moving down the Mississippi River from Cairo, looking for enemy entrenchments along shore, and any Confederate gunboats protecting them. In no time, the new timberclads found themselves the targets of fire from the shore, and attacks by Confederate gunboats. It's important to remember that these gunboat designs were new. There was almost no time to test and improve the designs, and the captains and crews had almost no experience sailing these boats or shelling shoreline defenses or fighting other gunboats. Yet it is clear that Roger and his crew on the Lexington, and in fact the whole flotilla, quickly rose to the challenge. Here are two official reports, one written by Army Col. Gustav Waagner, Chief of Artillery, to General Ulysses S. Grant, and the other written by General Grant to General John Fremont, praising Roger's leadership.

As more gunboats were built, Roger was given command of a new ironclad gunboat, the Cincinnati. As Captain of the Cincinnati, he and his flotilla engaged the Confederates in a number of skirmishes along the Mississippi River.

On February 6, 1862, Roger's flotilla was assigned the task of assisting the Army in attacking the Confederate forces at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. The flotilla was one prong of a two-pronged attack. The other prong consisted of Union Army troops under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant. The gunboat flotilla was under the command of Admiral Andrew Hull Foote, Flag Officer. Admiral Foote selected Roger's ironclad Cincinnati to be his flotilla's flagship for the attack.

The Cincinnati led the attack of Fort Henry, however it became obvious that theirs was the only prong attacking. The Army, approaching the fort from another direction seriously underestimated the depth of the mud on the roads they were to take and so were significantly delayed. Without the Army, the battle was entirely in the hands of the Navy gunboats. The Cincinnati was hit 31 times, with one crewman killed and nine wounded. Finally, the gunboats' superior firepower overwhelmed the Confederate troops defending the fort, and Fort Henry surrendered...before the Army even had time to attack! Roger, as Captain of the flagship, represented Admiral Foote and accepted the surrender of General Lloyd Tilghman (who also was represented by a subordinate)(7).

In early May, this Union gunboat flotilla was back on the Mississippi River where they were ordered to engage in a daily bombardment of Fort Pillow, on the Tennessee side of the river. Fort Pillow was heavily fortified and was blocking the Union fleet from going downriver. Every morning a Union mortar boat was towed downriver to bombard the fort. It was protected by one of the flotilla's ironclads. On the morning of May 10, that duty fell to the ironclad Cincinnati, under the command of Commander Stembel. About six o'clock that morning, a Confederate fleet of eight vessels attacked the Cincinnati and the mortar boat they were protecting. The Cincinnati was rammed first by the Confederate vessel, General Bragg, then the vessel Sterling Price, and finally by the Sumter. Before being rammed by the General Bragg, the Cincinnati was able to swing her bow around, so the first hit was just a glancing blow. The next two hits, however, seriously damaged the Cincinnati. At some point during the battle, Commander Stembel left the safety of the wheelhouse to go out on the deck to rally his men. According to a newspaper account, Commander Stembel drew a revolver and shot the Captain of one of the rebel vessels, but as he was turning to return to the pilothouse he was shot in the back by a sharpshooter aboard the Confederate ship Sumter. The projectile entered his back near a shoulder blade, passed through his neck, and exited just under his chin. Commander Stembel was carried below decks, thought to be dead or mortally wounded.(8) Roger's son, James, was on board at the time serving as a Master's Mate. He was only 15 at the time. It must have been very upsetting to see his father carried below deck bleeding profusely from his back and throat. Roger survived. He spent the next two years in Philadelphia recovering and returned to active duty after the war(9).

On February 22, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln wrote, "These extracts of letters of Admiral Foote show Commander Stembel to be a very meritorious officer. Unless the Sec. of the Navy knows some reason to the contrary, I propose that a vote of thanks be taken of Congress for him. If there be nothing in the way, please send the papers to sign."

Click here for a chronology of Roger's activities during the war, and to read two newspaper accounts of his wounding.

In 1866, almost fully recovered, Roger was promoted to Captain. He was promoted again in 1870, to Commodore, and made Commander of the U.S. Naval Squadron in the South Pacific. In 1872 his fleet was at anchor in the Bay of Callao, Peru, when on July 22, during an election of a new government, Peru's Minister of War along with some military troops loyal to him, tried to overthrow the government. Commodore Stembel observed this and immediately reported it in detail to the U.S. Secretary of the Navy. His lengthy report was published in the London Times(11) and no doubt in other major newspapers around the world.

Roger retired in December of 1872 with the rank of Commodore. He was 62 years old. In 1874, by a special act of Congress, he was promoted to Rear Admiral.(12)

After retirement, Roger and Laura traveled to Europe frequently. They also summered at Narragansett Pier, a resort town in Rhode Island. When not traveling, their main home was the Ebbitt House, a hotel in Washington, DC, where many retired Naval officers resided.

Roger died of pneumonia on November 20, 1900, in New York City. His wife, Laura, died one month later. Admiral Stembel and Laura are buried in Arlington National Cemetery, across the river from Washington, D.C. Forty-three years after his death, the Navy honored him by launching a new destroyer named after him, the USS Stembel (DD-644), launched May 8, 1943, at the Bath (Maine) Iron Works.(13)

Roger and Laura Stembel's two children:

At the age of 19 Clara married Charles D. Schmidt on January 20, 1863, in Hamilton County, Ohio. Charles was a wealthy wine importer from New York (in the 1870 census, Charles' personal estate was valued at $100,000). Charles was more than 10 years older than Clara. He was born in New York, but his parents were born in Germany. They had a daughter, Laura, born sometime around 1866 in Ohio (based on information in the 1870 census). Fifteen years later they had a son, Paul Stembel Schmidt, born in December 1880, but he died less than three months later.

Between the birth of their daughter in Ohio and the 1870 census, Clara, Charles and Laura moved to New York City. Then between the 1870 and 1880 census they moved to St. Paul, Minnesota. The census shows they were living with Clara's parents in St. Paul. An 1885 Minnesota state census shows Clara, Charles, and Laura were still living in St. Paul, but not with Clara's parents.

Between the 1885 state census and the 1900 federal census Clara and Charles moved back to New York, where Charles died on April 16, 1898. Admiral Stembel's obituary described Clara as a widow residing in New York City.(14) When the Admiral's wife died two weeks later, her obituary noted that she had died at Clara's home where she was convalescing. Strangely, I have not been able to locate Clara in the 1900 census records though she was reported in her mother's obituary as living at 35 West 25th Street in New York. In fact, I have not been able to find any records of Clara after the death of her father and mother in 1900. It is possible they moved to Europe, where her father and mother frequently visited, and her brother died in 1907.

Clara and Charles's children:

1. Laura Stembel Schmidt. Laura was born in New York City on April 27, 1866. On August 26 of the same year she was baptised at St. Ann's Episcopal Church for the Deaf. This would imply that Laura was deaf, but neither the 1870 or the 1880 census indicated she was deaf (there was a column on the census form where that was supposed to be marked). When she was 17, Laura accompanied her Grandparents (Admiral and Laura Stembel), and her mother, Clara, on an extended trip around Europe. Her father didn't accompany them, which is strange because he was born in Germany. I have found no record that Laura ever married, and the last record I have of her is in 1902 when she was mentioned on the society page of a New York City newspaper.

2. Paul Stembel Schmidt. Paul was born in December 1880, in St. Paul, Minnesota. He died three months later.

As a teen-ager James served in the Civil War as an Aide to Admiral Foote. As a reward for his service Admiral Foote secured a position for James at the U.S. Naval Academy, but James didn't thrive there and left the Academy in 1865. The next year he apparently traveled to Europe with his mother. His passport application describes him as 5' 8" with blue eyes and brown hair.

On October 19, 1867, James entered the Army as a 2nd Lieutenant. He was assigned to the 27th Infantry. His first post was Fort Kearney in Nebraska. Fort Kearney was situated on the Platte River and the Oregon Trail. At the time James was stationed there it served as protection for the workers building the Union Pacific Railroad. A year later James was put in charge of Company F and sent to Fort Reno in present Wyoming (northeast of the present town of Kaycee) to help decommission the small fort. In June 1869, he transferred to the 9th Infantry and sent to Fort Bridger, also in Wyoming, where he was stationed at the time of the 1870 census. Later that year James and Captain Robert Montgomery led a contingent of 30 troops from Fort D.A. Russell as an escort for an expedition from Yale College (now University) looking for dinosaur fossils in the West. Among the students who were on the expedition was Eli Whitney, grandson of the inventor of the cotton gin, and George Bird Grinnell, later to become a famous early conservationist and founder of the Audubon Society.(15)

In 1873, James was still a 2nd Lieutenant, and Commander of Company I of the 9th Infantry, stationed at Fort Rice on the Missouri River (about 30 miles south of present day Mandan, North Dakota). On June 20 his company became part of a large expedition, known as the Yellowstone [River] Expedition of 1873(16). The purpose of the expedition was to protect a team of engineers from the Northern Pacific Railroad from the Sioux Indians. The engineers were surveying an extension of the railroad west through the Dakota Territory and into the Montana Territory along the Yellowstone River. The Sioux were angered by the idea of a railroad extending into their ancestral lands. The expedition consisted of 1530 soldiers, 275 wagons, and 27 scouts from Fort Rice and Fort Abraham Lincoln, another fort along the Missouri River. Second in command of the expedition was Lt. Col. George Custer (who was killed three years later at Little Big Horn).

The expedition lasted three months and encountered torrential rain, a dangerous hailstorm, extreme heat, and flooded rivers. The expedition also experienced two attacks from Sitting Bull's Sioux warriors. The battles were relatively minor with a few casualties on both sides, but the army prevailed in both and the Indians eventually retreated, allowing the engineers to complete their survey(17). There is no indication that James participated in either battle.

On November 10, 1875, James married Louise Deshler, the daughter of a wealthy banker in Columbus, Ohio. This was Louise's second marriage. She brought a child, Clarence Penn-Gaskell Woodrow(18), to the marriage whom James legally adopted, thus Clarence went by the name Clarence Stembel all his life. We know of at least two children born to James and Louise, one in 1876, the other in 1878, but both died just days after their birth. Both are buried in Green Lawn Cemetery, in Columbus.

James was promoted to 1st Lieutenant in 1879. In the 1880 census he was enumerated at a small outpost in Carbon County, Wyoming Territory. Louise was not living on post, in fact I haven't found her recorded anywhere in the 1880 census. An 1882 newspaper article indicated that both James and Louise were living at Fort Omaha, Nebraska.(19)

James spent his entire career in the Army, retiring in 1890 with the rank of Captain. He spent almost his entire time in the Army stationed at forts in the west. After his retirement it is not known what James and Louise did or where they lived. They are both absent from the 1900 census, although James was reportedly at his father's side when he died in New York City later that year(20). Other than that mention in his father's obituary, I have found no record of James and Louise from the time of his retirement until their deaths. Louise died in 1904 at Atlantic City, NJ, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. She was 59 at the time of her death. James died three years later in Pau, France, and is reportedly buried there. I'm curious why James wasn't eventually re-buried in Arlington National Cemetery with his wife and parents.

James' adopted son, Clarence, was about seven when his mother married James. At some point he was enrolled at the Shattuck Military School in Fairibault, Minnesota, where he graduated in 1887. Soon after graduation he was hired by the Chicago Great Northern Railroad as a clerk, living in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was the beginning of a long career with the railroad. By 1896 he had been promoted to an assistant to the general manager of the company. By 1900 at the time of the census Clarence was living in Oelwein, Iowa. His occupation was recorded as "railroad agent." Later that year he married Marion Lamprey, a granddaughter of the founder of the St. Paul (Minnesota) Pioneer Press newspaper.(21)

Marion Lamprey, now Marion Thienes, had recently returned from Europe with two young children from a first marriage, Alvin and Dorothea Thienes. Evidently her husband, a German, had died soon after their second child was born, for her marital status in the 1900 census is recorded as "Widowed." Both of her children were born in France. I assume Clarence formally adopted them, because both children used the Stembel last name.

With the prospect of a new wife with two young children, Clarence had a new house built at 2530 Forest Drive in Des Moines(22). The house is still standing, and was recently renovated. The owner kindly sent a picture of the renovated house. Clarence's career continued to advance. In 1905 he was promoted to Superintendent of the Eastern division of the Chicago Great Western Railroad. In his new position he had use of his own private railroad car which he used to travel around his division inspecting facilities and conducting railroad business. On a return trip from Chicago in 1907, the train his car was attached to was involved in a bizarre and deadly accident. See the following footnote for more about the accident(23).In 1909 he took a new position, Superintendent of the Minneapolis & St Louis Railroad. This position required him to move his family back to the Twin Cities, this time in Minneapolis. Sometime around 1920 Clarence formed a company with Claude Siems, the Siems-Stembel Company, that refurbished railroad cars. After about five years they sold the company to the Standard Steel Car Company, and Clarence took an executive position with the Virginian Railroad Company where he worked until he retired. After he retired, Clarence and Marion moved to La Jolla, California where he died in 1939. After Clarence's death Marion moved to Pasadena where she died in 1954.

Clarence and Marion's two children:

1. Alvin Lamprey Stembel. Alvin was born Alvin Thienes on February 16, 1894, in France, although his father was German. His father evidently died about three years later and Alvin's mother, an American, returned to her home in Minnesota in 1898. In 1901 his mother married Clarence Stembel who adopted Alvin, thus changing his last name to Stembel. For some reason Alvin never acknowledged having been born in France or that his father was German.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1917 Alvin was required to register for the draft. The registration describes him as short, medium build, gray eyes and brown hair. He was working as a mechanic for the White Motor Company in Dallas, Texas. While living in the Texas/New Mexico area it appears that Alvin met and married Edith Josephine Lowe who was from New Mexico. Alvin and Edith were married in her hometown of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1918. After the wedding they went back to Texas to live, which is where their first child, Marion, was born in 1920. They soon moved to the Twin Cities where Alvin grew up. There they had their second child, Amelia, in 1922.

Sometime before the 1930 census their marriage broke up, because Alvin was living alone in an apartment in St. Paul and Edith was absent. Their children, Marion and Amelia, were living with Alvin's mother and step-father nearby. To complicate matters, living with Alvin was a maid, 24-year-old Phyllis Johnson. Not surprisingly, they soon married. They lived in the Minneapolis area for the remainder of their lives. Phyllis died in 1954 and Alvin in 1956. I don't believe they had any children of their own.

Passenger lists show that Alvin's mother, Marion, visited France in 1929, accompanied by Alvin and Edith's daughters, Marion and Amelia. Alvin's mother, Marion, again visited Europe in 1935. The passenger list of their return voyage shows she was again accompanied by granddaughter, Marion, but not Amelia (Amelia may have remained in Europe to attend school). Articles in the Albuquerque newspaper in the late 1930s indicate that Marion and Amelia returned to New Mexico in the late 1930s to live with their mother, Edith. All three used the Stembel last name. As a child Marion's name was spelled "Marian" probably to avoid confusion with her grandmother, Marion, but as an adult she spelled her name with an 'o'.

In 1940 at the age of 20, Marion married 26-year-old H. Robert Bras. They had some children, but I haven't found records of their births as of this writing. Amelia married Lt. Robert W. Andrea in March 1944. Robert was in the Army and soon after they were married, John was sent overseas where he died in the Battle of the Bulge. Sadly, Amelia was pregnant with his child at his death. Their daughter, Christine, was born a few months later. Two years later Amelia met and married Willard "Bill" Curtis Fales. Bill was a civil engineer who was also in the Naval Reserve who was called to duty during the Korean War. His civilian job and naval duty sent Bill all over the world, with Amelia by his side. After he retired they continued to travel extensively. Bill was a father to Christine and him and Amelia had a child of their own, Ralph Stephen Fales, born in 1951. Both Ralph and Christine married and had a number of children.

2. Dorothea E. Stembel Groff Horne Dorothea was born Dorothea Thienes in France in May 1896. We believe her German father died soon after her birth. Her mother, Marion Lamprey Thienes, returned to her home in Minnesota in 1898 with her two children. Three years later her mother married Clarence Stembel in 1901, who adopted both of Marion's children, so Dorothea's name was changed to Dorothea Stembel.

In May of 1915 Dorothea married Richard Llewellyn Groff. They had a son Richard, Jr. and a daughter, Nancy. Evidently the marriage ended sometime in the 1920s for in the late 1920s Dorothea married Owen E. Horne. They had a son, Owen, Jr., in June of 1929. In the 1930 Census they were living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. In September 1935, a passenger list for the S.S., Veendam, shows that Dorothea, her mother, and her daughter by her first marriage, Nancy Groff, and her niece, Marion Stembel, sailed from Europe (Rotterdam) to New York. Dorothea died a year later on September 4, 1936. I know little about Dorothea's three children. Richard Groff was a flour salesman in Minneapolis in the 1940 census, and Owen Horne, Jr., died in 1955 at age 26 in Los Angeles.

1. Henry named his son Roger after Revolutionary War veteran General Roger Nelson, according to an earlier Stembel family historian, Dr. William McLean. General Nelson was a family friend of the Stembel's. He named one of his sons Frederick Stembel Nelson (1803-1823).

2. Roger's land purchase was described as the "north west quarter and west half of the north east quarter of section nine in township three of range six east in the district of lands offered for sale at Cincinnati, Ohio, containing two hundred and thirty nine acres, and fifty six hundredths of an acre." Today the description would be more descriptive, Township = 3 North, Range = 6 East, Prime Meridian = West of the Great Miami. This puts Roger's 240 acres in the middle of today's Dayton's International Airport.

3. "James McBride," Masters Thesis by Francis Richard Gilmore. Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. 1952.

4. This information was provided to me in a letter dated January 12, 1998, from Dr. Robert S. Wicks, Professor of Art History, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio.

5. The Executive Documents, Printed by Order of the Senate of the United States. First Session of the Thirty-Sixth Congress, 1859-60. Volume 10. p. 281, 296.

6. This letter is held in the Missouri History Museum. It has been scanned and posted online as part of the "Confluence and Crossroads - The Civil War in the American Heartland" collection hosted by the Southeast Missouri State University Special collections and Archives. It can be viewed online at:

http://semo.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/Civil_War/id/2733/rec/1

7. David Maynard Stembel, "An Account of the Naval Career of Admiral Roger Nelson Stembel." Unpublished paper written at the United States Naval Academy, 1953. p. 10.

8. Bearss, Edwin C., Hardluck Ironclad. Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 1980. p. 60-61.

9. May 10, 1862: "Captain S[tembel] was aiming a pistol when a ball entered his right neck, broke the hyoid bone, and traversing the the neck emerged...through the edge of the trapezious muscle. He fell, half conscious and confused, but soon reviving, felt that both arms were paralyzed. ... [H]e was carried below in great pain, and spitting blood freely..."

"...His medical attendant...writes as follows: When first seen by me [19 May 1862] the anterior wound was discharging mucus and pus, with saliva. His voice was hoarse;...his left arm was still still slightly paralyzed, having rapidly improved. On the right side the deltoid, the biceps, and brachialus anticus were completely paralyzed,... Up to [this date, 9 July 1862, have improved very little. The muscles of the right forearm are nearly as much paralyzed as those of the arm...Captain S[tembel] seems to have lost to a great degree, the use of most of his shoulder muscles on the right side."

Captain Stembel eventually recovered his normal voice. His convalescence was interrupted by accidents and a bout of pnuemonia. He continued to be treated for three more years, and by October 1865, he was almost completely healed. At that time he was well enough to be given a new command and was back out to sea..

New York Medical Journal, Volume 2. p. 407-409. 1866. John Medole, Printer. 4 Thames St., N.Y. [Downloaded from Google Books, January 23, 2020]

10. C.M. Bell, photographer. Adml. R. N. Stembel., None. [Between 1873 and 1890] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016688178/.

11. "The Times [London]," September 3, 1872, pg 5, "The Revolution in Peru".

12. Hamersly, Lewis Randolph, The Records of Living Officers of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. New York: L. R. Hamersly Co., 1902. p. 26-7. According to this source, Roger Nelson Stembel was promoted to Captain in 1866, to Commodore in 1870, and Rear-Admiral in 1874.

13. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Volume VI. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy, 1976. p.614-5. U.S.S. Stembel received nine battle stars for World War II service and three for service in the Korean War. In 1961, the U.S.S. Stembel was loaned (and later sold) to the Republic of Argentina and renamed the Rosales. In 1985, I called the Argentine military attaché at their Embassy and found that the Stembel/Rosales had been scrapped. The attache, sensing my disappointment, explained, "He was a very old ship, Sir."

14. "New York Times," November 21, 1900. Obituary of Rear Admiral Roger Nelson Stembel. On microfilm in the Library of Congress. Clara was by her father's side when he died. She was described in the obituary as Mrs. C. D. Schmidt, a widow.

15. I found this on University's Peabody Museum of Natural History website (1/24/2020: https://peabody.yale.edu/collections/archives/yale-college-scientific-expedition-1870.

16. Report on the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873. By United States War Dept; Stanley, David Sloane, 1828-1902. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1874.

https://archive.org/details/reportonyellowst00unit

17. Ironically, the Panic of 1873 forced the Northern Pacific Railway's backers (such as Jay Cooke) into bankruptcy. This halted construction of the railroad through the Sioux territory for another 12 years.

18. Penn-Gaskell is an unusual middle name. Given that it was conferred to Clarence in 1868, it may refer to William Penn Gaskell, a lesser-known radical activist in England who advocated for universal suffrage for men and women (which was not the case in the 1850s in England) and other progressive ideas. For a biography of William, see www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/william-penn-gaskell-1808-1882/

19. About this time, an interesting story was unfolding. In January 1878 the wife of Louise's half-brother, John Green Deshler, was very ill and expected to die soon, which she did on January 12. But five days before her death, her husband (Louise's half-brother) walked down the front steps of their home in Columbus, Ohio, and dropped dead. It should be noted that John Green Deshler was very wealthy, and that he and his wife had no children. Thus, both of their wills donated most of their estate to charities.

However, in those intervening five days, a new will was suddenly drawn up by John's dying wife. In the new will most of her estate was left to her relatives. In a not so strange coincidence, her brother, who was a major beneficiary of the new will, just happened to be by her side as she wasted away in those last five days. Anyway, the original beneficiaries - one of which was Louise Deshler, James McBride Stembel's wife - filed suit. I don't know what the court ultimately decided but a newspaper at the time lamented that the only winners would be the lawyers arguing the case.

20. "New York Times," November 21, 1900.

21. "St. Paul Pioneer Press," April 21, 1954. Obituary of Mrs. Clarence (Marion Lamprey) Stembel. On microfilm in the Library of Congress.

22. The house is still in use and was recently renovated. The owner kindly sent a picture of the house as it looked in 2012.

23. In the early morning hours of February 6, 1907, an overnight express train traveling west from Chicago, missed a signal approaching German Valley, Illinois, jumped the track and caromed down a steep embankment where it smashed into a grain elevator filled with a 100 tons of wheat. All that wheat dropped down on top of the engine, mail cars, and some passenger cars. It completely covered them, making rescue of those trapped underneath nearly impossible. Meanwhile the surviving passengers struggled to escape only to confront a bitterly cold February night. There they huddled and waited until a rescue train with doctors and nurses could get there from Rockford, a likely wait of two hours at least. Clarence's private railroad car was attached to the train and he immediately took charge of the situation. With his authority, he was able to cut through the red tape and get quick action.

After the doctors in the rescue train treated the injured, the the worst injured were loaded into the rescue train and started for Chicago, but before they got there, the rescue train hit a horse and buggy on a crossing in Glen Ellyn, killing the horse and seriously injuring the driver. [Chicago Daily Tribune. February 8, 1907]

Return to the top of this page

Copyright. Oren Stembel, STEMBEL FAMILY HISTORY PROJECT (familyhistory.stembel.org).